Snorkelling and coasteering in Paraggi Bay, Portofino: 5 interesting facts about the flora and fauna

Some fascinating facts about the unique biodiversity hidden just above and below the tide in Niasca and Paraggi Bay in Portofino.

By now you know how we work: sport for us is a way to discover the nature around us from the inside, with respect and curiosity. Because just as we said to you in the last blog post and as David Attenborough reminds us: “No one protects something that doesn’t interest them, and no one is interested in something that they haven’t experienced”.

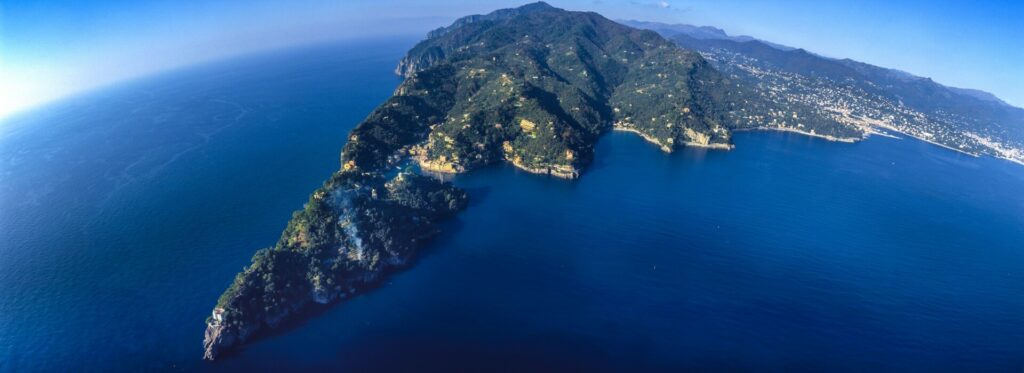

Plus we also have the privilege of living in a unique location and are strictly connected to our territory. One of our values in fact is that of belonging: to our planet and our earth (and sea). The Portofino promontory is a little bit like an island, joined to Liguria by a thin strip of land. Its microclimate, history and biological and geological make-up create a unique nature setting in the Mediterranean, not far from our home. The Mediterranean scrub characterizes its coasts, together with the Regional Park, and the promontory “dives headfirst” into a sea that teems with wildlife, protected thanks to one of the best managed Protected Marine Areas in Italy.

Founded in 1999, the Portofino Protected Marine Park extends for just over 3.5 km2 over the towns of Camogli, Santa Margherita Ligure and Portofino, enclosing some of the most protected, studied and interesting places in the Med.

Niasca Bay

Our headquarters are found right in the centre of the Portofino Protected Marine Park, in a bay named Niasca inside Paraggi bay. The first time that I went to Niasca, I was enrapt by its contrasting colors immediately: the harlequin light brown colors of the Portofino conglomerate rock, the bright green of the vegetation by the sea, the turquoise water above the white sand and the intense watery green of the bay itself. Indeed, thanks to its unique geographical position, this tiny bay offers various microhabitats.

On the sides of the bay we find two rocky cliffs, very different from each other because of how the varying illumination characterizes them: the right hand cliff (exposed to the Southwest) is shaded, thanks both to the shelter that the vegetation offers and to the exposure, making it a unique place to observe the organisms typical of grottoes and poorly lit areas, whilst the left hand cliff (exposed to the South) is very light. On the other hand, in the centre of the bay we find a vast and luxuriant Posidonia oceanica seagrass prairie (and if the name flummoxes you don’t worry, we will soon explain all about it), which with its fronds gives that typical color that inspires the pantone Paraggi green. At the outer limits of the seagrass field, in front of our headquarters and around the rocky cliffs, is the extremely white sandy seafloor. Three habitats which are quite different from each other, home to animals that are extremely diverse from each other.

In fact in the sea, the race for space is hard won, and each organism has evolved to exploit better the area available to it: there are those who have learned to live on the seafloor, whether it be sandy, rocky or muddy, those who swim into the blue, making the most of its length, width and depth, and still more others who wander the seas without any apparent direction, acting as one of the main engines of diversity.

Niasca, because of its unique geographical position, its exposure – sheltered from the prevailing winds – and habitat diversity, reveals itself to be a treasure chest of biodiversity, both above and below the tides. And the greater the coastal biodiversity, the greater is the ability that the sea has to cope with disturbances like climatic changes. For this reason we should imagine it to be like a treasure hunt, but at the end, instead of the crock of gold, we put the most important treasure on our planet: the diversity of its living species.

So we choose our favourite sport in order to explore the coast – let’s dive in and explore Niasca bay’s biodiversity.

1. Plants or seaweeds?: from the corals to the Posidonia

Certainly as soon as we hear talk of barrier reefs, we close our eyes and imagine stretches of tropical corals, highly colored fish and beached in the Maldives, But at the rocky edges of Niasca Bay we have what Luca, founder and CEO of Outdoor Portofino, calls “la barriera corallina de no’ artri” (translated from the Genoese dialect, “our homegrown barrier reef”). This is coralligenous, a formation of encrusting seaweeds (often of a pink color) that create a 3d structure on the rock. Just like in a coral reef, animals find food and shelter in the habitat that these seaweeds create, and just like corals, these seaweeds grow very slowly, collecting and forming their calcium carbonate skeleton.

During coasteering excursions, we have exactly the opportunity to discover these incredible formations up close and observe the incredibly diverse life that finds its home here, a shelter for mussels, tiny crabs, sponges and mollusks. Plus you will have certainly heard of the whitening or ‘bleaching’ of tropical corals, when corals lose their symbiotic seaweeds – and with them their bright colors – due to raised water temperatures.

In a very similar fashion, when high temperatures, the sun and low tides coincide, coralligenous too is “bleached”, losing its pink and red tones, with the risk of drastically simplifying the coastal habitat and therefore limiting its biodiversity as a consequence. The more that climate change proceeds, the more will be the frequency and virulence of anomalous thermal events like marine heatwaves.

And if by any chance you think that all of the underwater flora is characterized by seaweeds, I’m afraid you’ll have to think again! Because the Posidonia oceanica that we talked about before, present in great seagrass prairies in the centre of Niasca Bay, is nothing but a plant! In fact a seaweed does not have roots or leaves, nor does it produce flowers or fruits: all elements that characterize the Posidonia, which flowers – with its beautiful sea daisies – produces round fruits that look like olives (but they’re not edible!) and loses its leaves in the autumn, just like the trees do.

And in the same way that birds decide to build nests in forest branches, many marine animals (amongst which many sorts of commercially sought after fish) use the posidonia as a nursery, where they give birth, hatch their eggs and have their little ones grow up. In fact if you get close to the Posidonia fronds in the summer, you can see lots of tiny electric blue fish, which are baby damselfish (latin name Chromis chromis).

And furthermore, every square metre of Posidonia releases around 20 litres of oxygen into the atmosphere, every day! Basically a treasure of biodiversity and a real “blue lung” for the planet, to discover with a mask and flippers during our snorkelling tours, or even just to look down upon during a SUP trip!

2. Sea “flowers” : anemones to track down

They are called Anthozoans, from the Greek άνθος (ánthos; “flower”) e ζώα (zóa; “animals”), owing to the flowery look that the animal has. They are polyps (and not octopuses, the intelligent eight-armed and three-hearted molluscs), and are nothing more than cousins of the jellyfish from the Cnidaria Phylum. Both whilst coasteering and when paddling, we can easily track down “sea tomatoes” (Actinia mediterranea) amongst the rocks, so-called because of their bright red color (but they’re not edible!).

To facilitate the mental step that we need to make to understand the relationship between a jellyfish and an anemone like the sea tomato, try imagining a jellyfish that has stuck its back to a rock…here you are, an anemone! The anemone’s tentacles also sting slightly, even though not as strongly as those of the common sea wasp jellyfish. The stinging cells help the anemone to feed, gathering the plankton that floats in the waves with its tiny tentacles.

Just a little further below the tidal line, equipped with mask and flippers, we can go ‘hunting’ other beautiful sea flowers.

Swimming with flippers on in the shade along the rocky coast (to the right of the bay, when facing out to sea), we might encounter a beautiful cushion coral (Cladocora caespitosa), a particularly interesting species given the various bleaching episodes (just like the corals that we talked about before). Always on the same rocky side of the bay, in some areas of the shade we can observe yellow cluster anemones (Parazooanthus axinellae), colonial anemones that form beautiful orange carpets.

3. The bay’s thorns: urchins and starfish

Containing our swim amongst the rocks, we are certainly attracted by the bright scarlet color of a Mediterranean red sea star (Echinaster sepositum), amongst the best loved animals on our snorkelling tour. An interesting fact about starfish is that they move around almost entirely due to hydraulic pressure: water enters a hole in the centre of the star and is then pushed into all of the arms (called pedicels), a bit like how an inflatable puppet moves at the entrance of a shopping centre. Exactly for this reason it is really important to never pull a starfish out of the water, not even for a few seconds. In fact, any air bubbles that get stuck in this hydraulic system could short-circuit their locomotion completely.

Even through aesthetically different, starfish are part of the large sea urchin phylum, and together with the sea cucumbers form the echinoderms (from the ancient Greek ἐχῖνος, echinos – hedgehog and δέρμα, derma – skin, because they are covered with spikes, more or less pointy and prominent). Inside Niasca Bay we can mainly detect two species of urchin, commonly called the black sea urchin (Arbacia lixula) and purple sea urchin (Paracentrotus lividus).

The common names are confusing but the scientific Latin nomenclature is much clearer: in fact, they are two completely different sea urchin species, and can be distinguished as the species with edible eggs (the purple one) and the one with non-edible eggs (the black one). Apparently similar, you can tell them apart thanks to some of their characteristics and colors. Should we want to attribute them with a personality to identify them more easily, we could say that the purple urchin loves wearing red (and in fact has a reddish color), whilst the black urchin is a little “timider”, liking to use pieces of seaweed and shells to hide itself better among the rocks.

Apart from having sharp spikes – so make sure that you take care when you swim near the rocks – urchins are also extremely important in terms of biodiversity. Scientists like us call them “ecosystem engineers”, exactly because by grazing the seaweed like cows in the pasture they leave portions of the rock free, which allows other animals to settle there, increasing the number of species and the biodiversity and complexity of the habitat. Exactly due to its importance and its commercial appeal, the purple sea urchin has been put on the list of species protected by the SPA/BIO protocol (Barcelona Convention), and in order to avoid indiscriminate collection, a Ministerial Decree was established (D.M. 12 gennaio1995) which regulates collection to 30 examples per person, with a total fishing block from May to June.

4. Life between the tides: from limpets to the unpopular barnacles

Who has never slipped over a rock and cut their foot? If you are an avid fan of rocky beaches, this has probably happened to you often enough. It is highly likely that your cuts were caused by barnacles, in Italian commonly known as dogs’ teeth. Differently to their cousins, limpets (mollusks with a traditional conical shell, of which the largest and most vulnerable in the Mediterranean is the Patella ferruginea), barnacles are not mollusks, but crustaceans (just like crabs and lobsters)!

The barnacle’s tale

To explain better exactly what a barnacle is, try to imagine this: think that many years ago a tiny prawn, during its evolutionary process, decided that it didn’t want to swim any more. It chose a rock, and cemented itself to it, directly on his head. Now in order to survive, an animal needs to do three main things (a bit like a human does): eat, not get eaten and reproduce.

To tackle the problem of not being able to swim towards its food any more, and as its little feet were no longer necessary, it modified them, making them more like feathers (and that’s where the Cirripedia name comes from) to move between the waves, capturing plankton and micro seaweeds. To avoid being eaten, it built a solid and voluptuous shell, from under which it pokes out the feathers and feeds itself, a bit like a superhero would when it comes out of its hideaway. And to reproduce, it had to face two problems: the need to reproduce sexually so as to be more successful in the evolutionary sense, and the necessity of having two individuals, despite the fact that each barnacle contains both male and female sex organs.

For this reason, it evolved to have the longest penis in proportion to body length of the entire animal kingdom, which it uses to reach individuals around it, either near or far. To sum up, yes, a lazy prawn, but very well-endowed!

5. The Bay’s fish

As we find ourselves inside a Protected Marine Area, fishing is prohibited in Niasca Bay, which plays host to a large quantity, abundance, size and biodiversity of fish species. In a well-managed protected area, the quantity (in terms of weight) of fish increases in fact by 446% and the biodiversity by 21%!

Amongst the many species of bream and wrasse, abundant damselfish, the elusive moray eel and the curious and brilliant king mullet, some of the most curious fish to spot while snorkelling are definitely the groupers. In the bay you can find mainly dusky groupers (Epinephelus marginatus), of both small and remarkable sizes. It’s not hard to identify them thanks to their brown colour with yellow spots, their particularly annoyed expression and their round pectoral fins which they wield with a fan movement. An interesting fact about groupers is the definition of their sex, which, as with many fish, is not genetic like it is for us: indeed, the grouper is a proterogynic hermafrodite, which means that at birth it is always female and becomes a male when it reaches a weight of around 8 kg.

The grouper, together with the tiny, brightly coloured Mediterranean rainbow wrasse (Coris julis) ornate wrasse (Thalassoma pavo), dreamfish (Sarpa salpa) and painted comber (Serranus scriba), are monitored in particular by the interregional project MPA Engage, because they are indicators of climatic change. Indeed, as the water temperature rises gradually there are many organisms that move towards higher latitudes seeking cooler waters or that, preferring warmer water, increase their distribution area. By monitoring the presence and abundance of these species, we can try to better understand the impact of climatic change on biodiversity in our Mediterranean Sea. During our marine ecology excursions, you too can also help us to monitor these fish by practising citizen science.

Recounting in just one blog the extremely rich biodiversity of Niasca Bay or all of the stupendous curiosities that regard the marine world is impossible – for everything else, we will await you in the water, to discover and experience the place in person!

N.B.: the beautiful slides in this presentation were prepared by Sophie, who during her internship worked as a snorkelling guide, to tell the story of Niasca Bay.